The Dortmund-Ems canal

The Dortmund-Ems canal was the most important transport route between the North Sea and the industrial coal-mining and steel-producing area of the Ruhr Valley. Its subsidiary, the Mittelland canal, joins the Dortmund-Ems at Gravenhorst, north of Munster. These canals had been recognised from early on in the war as prime targets – making the canals unnavigable would deprive the Ruhr of vast quantities of materials which were vital to the country’s war effort.

The most vulnerable point on the whole of the canal was near Ladbergen where it ran in an aqueduct over the River Glane - any breach would cause the water to drain onto the surrounding farmland however doing this meant very precise bombing, something which neither the RAF nor the USAAF were very good at until the latter stages of the war.

Attacks early on in the war on the canals were by medium bombers such as Handley Page Hampdens, indeed in August 1940 Flight Lieutenant Learoyd of 49 Squadron won Bomber Command’s first VC for pressing home his attack in the face of accurate and withering fire from anti-aircraft guns, for the canals were heavily defended from even those earliest days.

A map and photo-reconnaisance detail from the National Archives illustrating the vulnerable part of the canal near Ladbergen and the course of the Glane passing beneath, particularly noticeable in the photograph which has salient features marked on it by operational research experts .

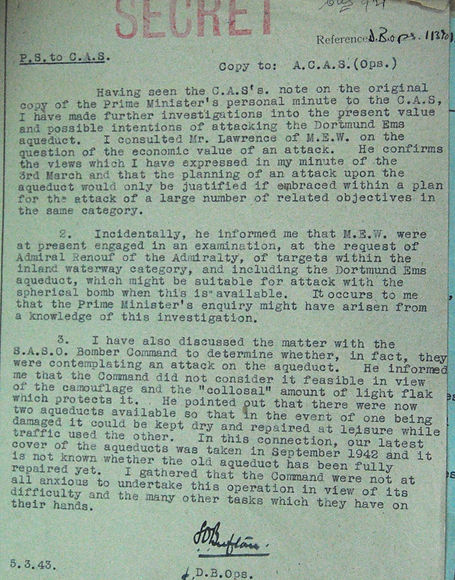

1. In March 1943, wishing to leave no stone unturned in what was known as the Transport Plan, ie attacking all the enemy's lines of communication, the Prime Minister sent a memo asking his advisers about the viability of attacking the canals once more:

2. This prompted a flurry of activity from various departments offering advice and statistics about the target:

3.....including the ground defences but not the threat of fighter attack! The significance of the guns bearing in the 120 - 250 deg arc was important; to ensure maximum effect the bombers could only attack from one direction - the Germans knew this and were ready.

4. Recently promoted Air Commodore Sydney Bufton DFC, Director of Bombing Operations and himself an experienced bomber pilot in the early years of the war and a known antagonist of Sir Arthur Harris and his area bombing policy, was measured in his response to Churchill's enquiry......

5. ..and further qualified his recommendation not to consider the aqueduct a worthwhile proposition....

6.......finally concluding that the risks involved outnumbered the benefits.

The importance of the canal for transporting industrial goods amongst others is illustrated by the figures shown in these documents prepared to help assess whether the risk of attacking it was justifiable:

Once the decision had been taken that it was a priority target, and once Bomber Command felt that it was in a realistic position to inflict significant damage to stop or at least inhibit the movement of these essential materials to the German war machine, no effort was spared from September 1944 until March 1945 when the canal was finally put out of action.

The view from the sharp end

Peter Barlow was a navigator in 463 squadron and a contemporary of Max and his crew. The following is an extract from “The Canals” which Peter wrote shortly after the war's end, his writing and observations give the sharpest appreciation and understanding possible of the thoughts of the crews when "Target Ladbergen" was announced at briefing:

Undoubtedly the most dangerous target during our tour of operations (November 1944 to April 1945) was the system of canals named Dortmund-Ems and Mittelland. This, and other obvious, and therefore heavily defended precision targets were beyond the true capability of Bomber Command at earlier times. Outside the range of supporting fighter aircraft and likewise beyond the range of the developing blind radio beam marking systems such as “Oboe” and “Gee-H”, there was no realistic hope of success with high level night-time precision bombing. Thus all the earlier attempts were carried out at low level in bright moonlight resulting in extreme vulnerability to point blank fast firing “light” (ie low calibre) anti-aircraft fire.

As Butch Harris says in his book, it was not until 1944 that circumstances made it possible to attack the target really effectively at a casualty level that was deemed acceptable (ie 5% or less) – acceptable to the chaps behind the desks that is, our opinions were not sought.

By this time the advances of the Allied armies had brought the target well within the range of radio target-marking aids, so the aiming points could be properly marked in weather conditions less than perfect. The efficient controlling of bombing and the great improvements in the accuracy of navigation meant that the whole operation could be accurately timed, enabling the attacking aircraft to be concentrated in a tightly packed “bomber stream” which could saturate the defences en route.

The particular problem of the canal targets was that even when an attack was successful, the Germans could immediately lay on a maximum effort to repair the breached earthworks and get the system back into use – and this work only took a couple of weeks. It was well known that a repeated attack would have to be carried out almost immediately the canal was opened to shipping. A hiatus of even a couple of days would enable the Germans to assemble a string of the delayed barges during the closure period and then rush them through the danger area in a continuous convoy before the next attack. And of course the universal awareness of these factors meant that the Germans knew precisely where and when the next attack would come, and it was this factor that made the target so desperately unhealthy. At the time on the squadrons we certainly knew that these two targets, Gravenhorst and Ladbergen, signified thoroughly “dicey” trips, but few of us had any real appreciation of the great strides the Luftwaffe had made in perfecting their capabilities and in thereby returning our physical danger to its former level. However it was not long before the evidence began to speak for itself.

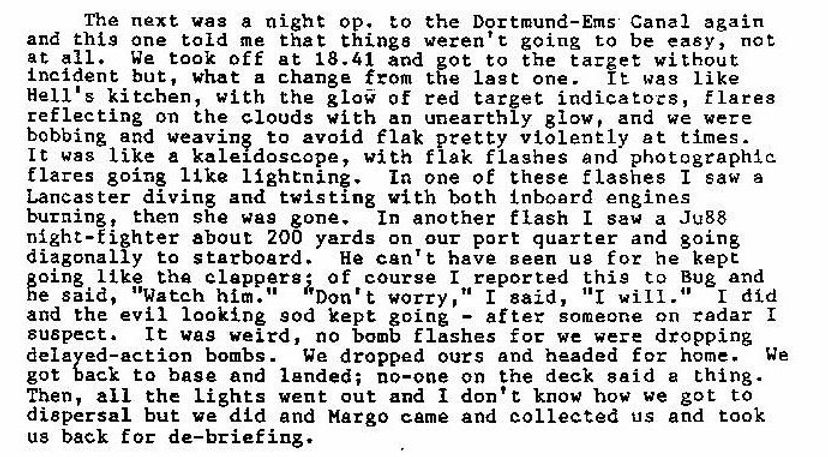

And that "evidence" is graphically described below by Cy (Cyril) March. Cy was a rear gunner with the Emery crew, they had arrived at Waddington from No. 5 Lancaster Finishing School shortly after the Ward crew on 9th February but Lady Luck dealt them a kinder hand. Cy is describing the attack on the canal on 3 March 45, so the stricken Lancaster that he saw could well have been ME453:

The Emery crew. Neville Emery, second from the left front row, hailed from Sydney and post war became an international rugby player, representing the Wallabies on their successful tour of England in 1947/8. He inherited the nickname "Bug" from his father, pronounced "Boog". To Bug's right is Terry Sayles, the navigator and standing between the two of them at the back is Cy. Cy, a Geordie, was a coal miner before the war and returned to the pits post war. The crew completed 15 operations before war's end.

The following extracts are from Australia in the War of 1939 - 45 Series 3 - Air (Vol IV Air Power over Europe 1944 - 1945 1st Edition 1963. Chapter 17: Bomber Command and the Transportation Plan: Spring 1945)